Abstract

This publication presents a consistent systematization of the compatibility between the pillars of modern physics and the NKTg Law on varying inertia. The NKTg Law is shown to be non-contradictory to classical theories, while allowing their dynamical structures to be abstracted into a unified state relationship among position, velocity, and mass.

Scope Statement

This publication focuses on establishing the conceptual consistency and compatibility of the NKTg Law with existing physical theories. The content is not intended to replace, refute, or claim full proof of any established theories.

Theoretical Basis

The NKTg Law describes the tendency of motion of a physical object through the relationship among:

• Position (x)

• Velocity (v)

• Mass (m)

General formulation:

NKTg = f(x, v, m)

The system is characterized by two core product quantities (unit: NKTm):

• NKTg₁ = x • p : positional inertia

• NKTg₂ = (dm/dt) • p : varying inertia

1. With Isaac Newton – Classical Mechanics

When the mass of the system does not vary with time, the NKTg Law reduces to a static inertial state.

• Condition: dm/dt = 0

• Consequence: NKTg₂ = 0

• Remaining expression: NKTg = NKTg₁ = x • p

In the context of classical mechanics and Newtonian gravitation, the quantity x • p preserves the structure of the momentum state, reflecting orbital stability and periodic motion.

In the limit of systems with large mass and velocities much smaller than the speed of light, the NKTg Law is structurally compatible, both in form and physical consequences, with all fundamental laws of classical mechanics.

2. With Albert Einstein – Relativity

In high-energy systems where mass and energy can be converted into one another, the NKTg Law extends into a regime of varying inertia.

• As velocity approaches the speed of light, energy and mass are related by E = mc²

• In this case: dm/dt ≠ 0 ⇒ NKTg₂ emerges and plays a dominant role

The NKTg Law describes the dynamical tendency of the system through changes in mass–energy states, without contradicting the fundamental relations of relativity.

In extreme configurations such as strong gravitational fields, the relative imbalance between NKTg₁ (associated with spatial structure) and NKTg₂ (associated with energy state) consistently reflects the phenomenology of relativistic objects, including systems with event horizons.

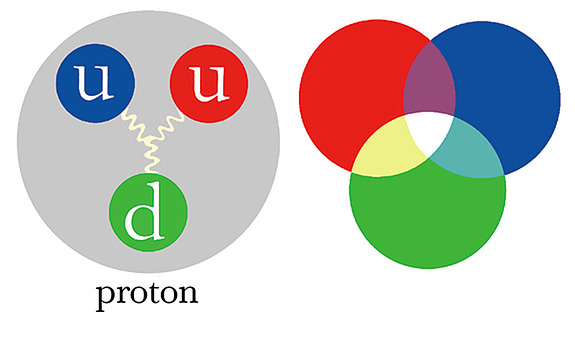

3. With Werner Heisenberg – Quantum Mechanics

At the microscopic scale, when considering particles with very small mass or mass approaching zero, the varying inertia component vanishes.

• Condition: m → 0 ⇒ dm/dt = 0 ⇒ NKTg₂ = 0

• Then: NKTg = NKTg₁ = x • p

In the quantum context, x and p are no longer interpreted as definite values, but correspond to uncertainties in position and momentum.

The expression x • p is structurally compatible with the Heisenberg uncertainty inequality (Δx • Δp) and does not violate the foundational mathematical form of quantum mechanics.

Conclusion: Synthesis of Physical Regimes

| Reference Frame | Representative Principle | Characteristic Condition | Dominant NKTg Component |

| Newton | Classical mechanics | dm/dt = 0 | NKTg₁ = x • p |

| Einstein | Relativity | Energy-dominated regime | NKTg₂ ≠ 0 |

| Heisenberg | Uncertainty principle | m → 0 | NKTg₁ (x, p) |

General Significance

The NKTg Law enables the stages of physical development to be described as different state limits of a single general dynamical relationship among position, velocity, and mass. This approach opens a unified and continuous perspective from the microscopic to the macroscopic scale, without breaking the foundational structure of existing physical theories.